The Fed’s Balancing Act: Why Rate Cuts May Be Off the Table Despite Easing CPI

Inflation Slows, But Not Sufficient to Tip the Scales

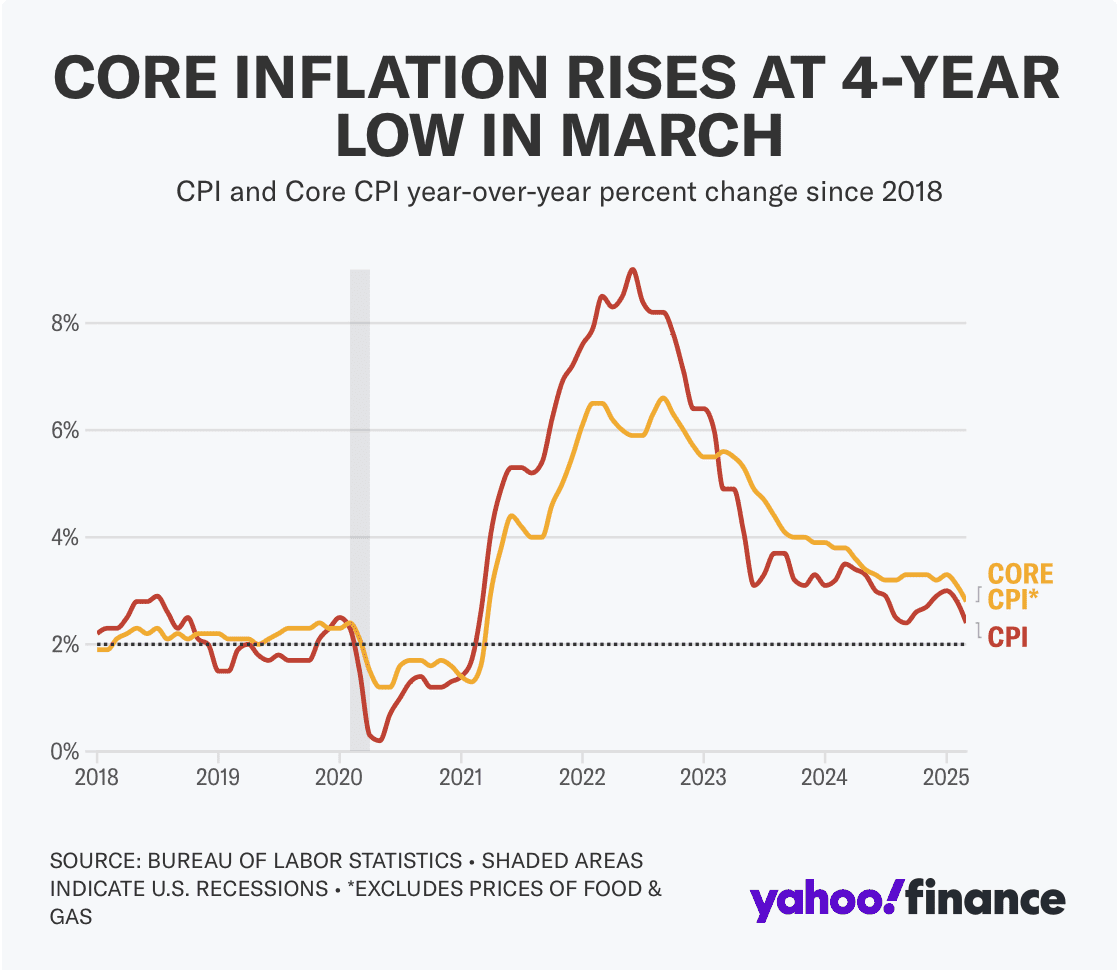

TradingKey - The March CPI report brought what looked like a victory: headline inflation cooled to 2.4% annual, and core CPI, which omits food and fuel, dropped to 2.8%, its lowest since this time last year. On a month-to-month basis, core inflation only increased 0.1%, a downtick from February's 0.2%. These are the types of numbers that will typically have Wall Street hoorahing and rate-cut fever running wild.

Source: Yahoo Finance

Yet, optimism is being tempered by reality. Prices have eased, yes, but not across the board. Core services inflation is still sticky, particularly for categories like housing, healthcare, and auto insurance. Those are steadier and harder to turn around with short-run policy levers. So, with this "cool" inflation print, there is little reason for the Fed to pivot.

Therefore, inflation is coming down, but not deeply and broadly enough to lead to rate cuts. The Fed requires sustained, multi-month declines in core inflation, not an occasional soft print, to begin easing policy.

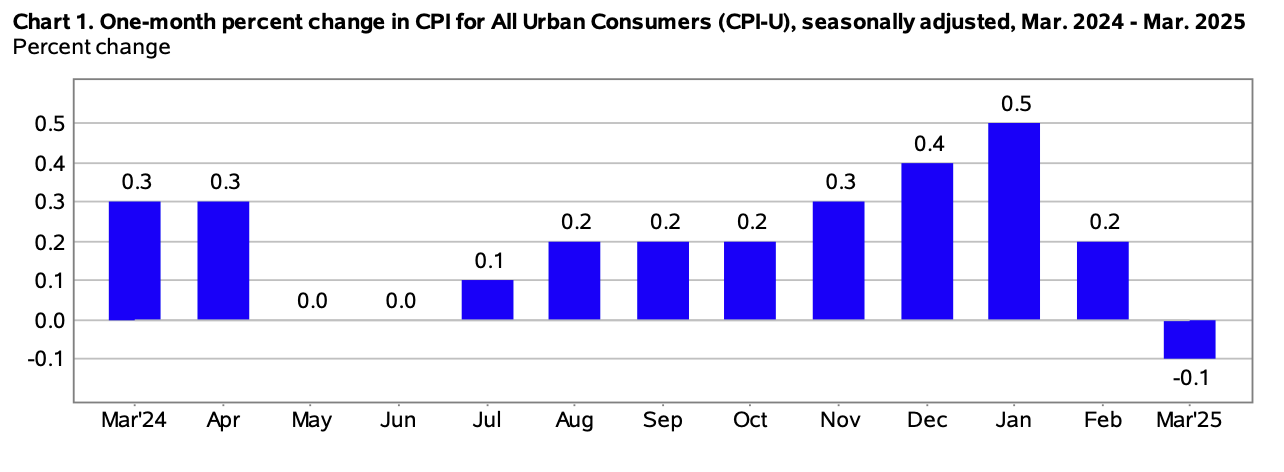

Source: Bureau Of Labor Statistics

Tariffs cast a shadow over the Fed's projections

Just as inflation starts to abate, there is an evolving new threat: tariffs. President Trump's return to tough trade policies, increasing tariffs to as much as 125% of Chinese imports, has many economists warning that inflation can again surge as early as Q2 or Q3. Some tariffs have been temporarily suspended for 90 days, but others still stand, and China has struck back with tariffs as well.

Historically, tariffs contribute to increased cost of imports, which companies tend to transfer to customers. It results in an increase in cost and fuel for inflation. Fed experts like Morgan Stanley's Ellen Zentner and PGIM's Tom Porcelli believe that recent CPI data is not a trend but an aberration.

Thus, the Fed anticipates inflation to increase once again as tariffs begin to bite. This alone justifies maintaining rates at this point, at least until policymakers can evaluate the complete economic impact.

The Fed's 'Patient Pause' Becomes Policy

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has used a cautious, measured tone recently, stressing uncertainty and patience. In his most recent statements, Powell said, “It is too soon to say what will be the appropriate path for monetary policy,” essentially signaling that rate reductions are not imminent.

It's a shared view at the Fed. San Francisco Fed's Mary Daly said the central bank could “take time,” while Minneapolis Fed's Neel Kashkari indicated that the threshold for rate cuts has heightened because of tariff-driven inflation risks. Even the March Fed's meeting minutes registered a strong bias toward caution, mentioning the problem with slower growth versus entrenched inflation.

The Fed is now in wait-and-see mode. Unless inflation declines and stays down, rates will probably remain steady for much of 2025.

Behind the Curtain: Services and Sticky Core Components

While there is a softening in energy and certain goods categories, the service sector continues to be a bastion of inflation. Housing costs have risen, healthcare and medical care services experienced a sharp increase in a month, and automobile insurance continues to be higher than last year. These categories are labor-intensive and linked to wage growth and hence are more difficult to slow with rate hikes alone.

It's important because core inflation is more likely to be long-running. It is not affected by temporary shocks such as oil price changes or supply chain dislocations. Rather, it is an expression of underlying economic forces, such as tight labor markets, that are difficult to quickly undo.

Lastly, provided that service inflation remains elevated, these risks will be considered by the Fed to be still unresolved. A couple of soft headline prints will not be sufficient to change policy.

A Difficult Trade-Off: Inflation Discipline vs. Growth Risks

America's economy is beginning to weaken. Hiring is slowing, business investment is levelling out, and consumer confidence is faltering. These are just the sorts of trends that under different circumstances would lead to future rate cuts to stimulate growth.

Nevertheless, Fed officials insist that price stability is a prerequisite for long-run economic well-being. Richmond Fed head Tom Barkin underscored that jobs will be sustainable only with steady inflation, and Boston Fed President Susan Collins noted that while reductions are feasible down the line, there must be a default position to remain firm.

The Fed will accept slower growth for a while to keep inflation at bay. Rate cuts will still be a last resort, not a baseline scenario.

Source: St. Louis Fed

The Bottom Line

While March's CPI update provided markets with a glimpse of disinflation, the Federal Reserve is not quite ready to turn around. With tariffs looming to undo inflation momentum, sticky core services, and credibility to protect, policymakers are telegraphing a cautious approach. Short of consistent, accelerating decline in inflation, and de-escalating geopolitical concerns, rate cuts remain far away.